Gothic literature, and more specifically gothic horror, is one of my great loves. I love the rain, the gloom, and it is my ultimate goal in life to retire to a creepy, possibly haunted, estate on some windswept moor at some point. I love the drama of gothic literature, the creeping dread that is always simmering just under the surface, the specters that lurk around every corner, the women in white nightgowns padding through darkened hallways by candlelight. If there is a haunted mansion and a brooding, mysterious stranger involved, I’m all in.

My earliest encounters with the genre were film versions of Dracula and Frankenstein which led me, as a voracious reader, to the source material. Since that time, I have come to hold a special place in my heart for the work of Mary Shelley, Shirley Jackson, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Oscar Wilde. Their stories fueled my imagination but they have also sparked in me an avalanche of questions—namely, what does gothic literature look like through the eyes of BIPOC and how do our often-intersecting identities fundamentally change the way gothic stories can be written?

We can and should love things critically. Gothic fiction has long been defined by its Eurocentric views and its obsession with class, race, and sexuality that favor the straight, white, rich people that fill its pages. What I love about the genre is that it is adaptable and how when taken up by writers like Poe, Shelley, and Stoker, it became something new and terrifying. Currently, we are seeing gothic fiction, particularly gothic horror, being remade once again, this time with a focus on characters from historically marginalized and excluded backgrounds.

The tentpoles of gothic fiction are an atmosphere of foreboding, a haunted place though the specters need not be ghosts, supernatural events, visions or synchronicities that serve as omens; high emotion; and a person, usually a young woman, at the center of the narrative who becomes the focus of the unexplained and often terrifying events unfolding around them. Gothic literature speaks to our fear and fascination with the unknown. As such, gothic literature has long been a foothold for the exploration of sexuality and has contributed to the way we think and write about queerness and not always for the good. Queer attraction in gothic literature is framed as one of the defining traits of the antagonist and death, in the form of self-sacrifice, was often seen as the only resolution. In the late 19th century, titles like Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde bolstered a rampant, almost hysterical atmosphere of homophobia by depicting queer characters as the “other”, as deviant and dangerous. I think it’s fair to say that some of these writers were working through their own feelings. Robert Louis Stevenson’s original manuscript was much more explicit about Dr. Jekyll’s motivations for essentially splitting himself in two. He culled from his final work these specific mentions of queerness but their absence only serves to further highlight Stevenson’s complicated feelings about Jekyll’s complicated truth.

In the Victorian era the gothic genre enjoyed a revival period; penny dreadful serial fiction was popularized making it more widely accessible to the public, and titles such as Varney the Vampire—in which vampires are shown to have fangs for the first time—introduced the tropes and settings that we now associate almost exclusively with gothic literature. It is in this time period that we see the publication of Woman in White, Dracula, Jekyll & Hyde, and The Picture of Dorian Gray—all works that deal with duality and duplicity, with what it means to be truly human. So what happens when we approach the creation of gothic literature with the specific intent of allowing characters who have been excluded or vilified in this space a central role? How does that change what gothic stories can convey? That we, as Black people and other people of color, as queer people, are largely absent from this genre except in the form of allegory, is not by accident; the racism in some of these stories is as clear as the blatant homophobia. Where do we go to find ourselves in this space? A novel by one of the most important figures in Black American literary history gave me a glimpse of what was possible for us in gothic literature.

“124 was spiteful. Full of a baby’s venom. The women in the house knew it and so did the children.” These are the opening lines of Toni Morrison’s 1987 novel, Beloved. This story has all the defining elements of a classic gothic tale and centers Sethe, a formerly enslaved woman who now lives in a house where the horrors of her past haunt her both literally and figuratively. This novel is set in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1873 and still evokes the kind of haunting atmosphere that defines the gothic genre. We see one of the cornerstones of gothic fiction take shape as the house at 124 Bluestone Road becomes almost sentient, capable of feeling spite and acting in kind and in tandem with the ghost of Sethe’s slain daughter. The unfathomable dread that permeates this tale is Sethe’s memory of her enslavement. Further, a gothic trope that Morrison expertly reimagines is the introduction of a long lost relative or a secretive and strange family member. The arrival of who Sethe believes to be Beloved in a physical body satisfies this narrative device with masterful execution. In this form, Beloved is strikingly beautiful and exudes a powerful, nearly irresistible sexuality. Beloved consumes so much of Sethe’s time and attention that Sethe begins to forget to take care of herself. This in turn leads to a draining effect, both emotionally and physically, and is reminiscent of the relationships gothic horror heroines often have with vampires. The tentpoles of gothic literature remain but the core narrative is made new when seen through the eyes of this Black woman. The gothic is redefined within the context of Black personhood. It was in Beloved that I saw what could happen when we bring our own cultural memory to a genre that has not made room for us.

Another piece of what is possible in gothic literature comes from the mind of Octavia Butler in her work, Fledgling. Vampires are a staple of gothic literature with Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla being the most prominent. In both stories the vampires are seen as existing outside of societal norms. Enter Shori, the main character of Butler’s story. She appears to be a 10-year old Black girl but is in fact a 53 year-old vampire. While her creation in Fledgling is based on a scientific experiment, the fact remains that we have a Black, polyamorous vampire at the heart of a story that explores race, sexuality, and our agency as individuals—all important elements in gothic storytelling. But here, Butler uses the tropes we’re familiar with and inverts them. Vampire narratives have long been allegories for xenophobic and homophobic beliefs. Vampires, with their pale white skin, are seen as the all powerful “superior” beings. Fledgling gives us a Black vampire whose relationship with her symbionts is beneficial to both parties, where her symbionts are nurtured and cared for, and where non heteronormative relationships are not only elevated but preferred.

So where do we go from here? As the gothic continues to evolve, expanding its reach, what we see consistently are works that not only redefine the established norms, but bring the genre to a place it has rarely been allowed to go before. Mexican Gothic by Sylvia Moreno-Garcia, Catherine House by Elisabeth Thomas, Spook Lights: Southern Gothic Horror by Eden Royce are all pulling from the gothic without being constrained by it. I am happy to see more of these stories being led by characters of color, by queer characters, and I’m extremely excited to see gothic YA and middle grade making strides in the genre.

I love a good scare, a haunting mystery, an air of impending doom, but beyond the thrill of the haunt, it is a place in which we can explore our true nature and discover what it means to be human. People from historically marginalized and excluded backgrounds know all too well what it means to have our humanity stripped away from us and as we gain more traction in the gothic genre we will do more than find bits and pieces of ourselves, we will find ourselves whole, made so by the telling of our own stories.

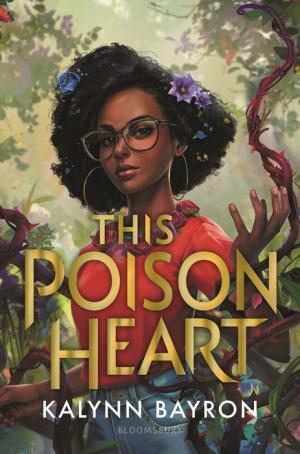

Buy the Book

This Poison Heart

Kalynn Bayron is an author and classically trained vocalist. She grew up in Anchorage, Alaska. When she’s not writing you can find her listening to Ella Fitzgerald on loop, attending the theater, watching scary movies, and spending time with her kids. She currently lives in San Antonio, Texas with her family.